The Aperspectival Geometric Art of Adi Da Samraj

Gary J. Coates, Professor

Victor L. Regnier Distinguished Faculty Chair

Department of Architecture

Kansas State University

Manhattan, KS 66506

USA

Professor Gary J. Coates is the Victor L. Regnier Distinguished Faculty Chair in the Department of Architecture at Kansas State University. He has published widely in scholarly and professional journals and is a frequent lecturer at conferences and universities in the United States and Europe. His five books include The Architecture of Carl Nyrén. He has been recognized for teaching excellence by the American Institute of Architects and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture.

Published in 2A Magazine Issue #12 – Autumn 2009

Introduction

For more than forty years, artist, scholar and spiritual teacher Adi Da Samraj (19392008) (see Figure 1)

was involved in the production of a unique, diverse and voluminous body of visual art including: Zen-like ink brush paintings; abstract color paintings; color and black and white underwater multiple exposure photographs; videographic suites synchronized with music, and; abstract geometric images and sculptures generated by digital technology.1

Adi Da’s purpose in all of this work was to create art which would enable the fully participatory viewer to experience at least a taste of the inherently blissful state of nondual awareness that he asserts is our native condition once we transcend the experience of being a separate “subjective” self perceiving a separate “objective” reality.

Transcendental Realism: The Art of Adi Da Samraj

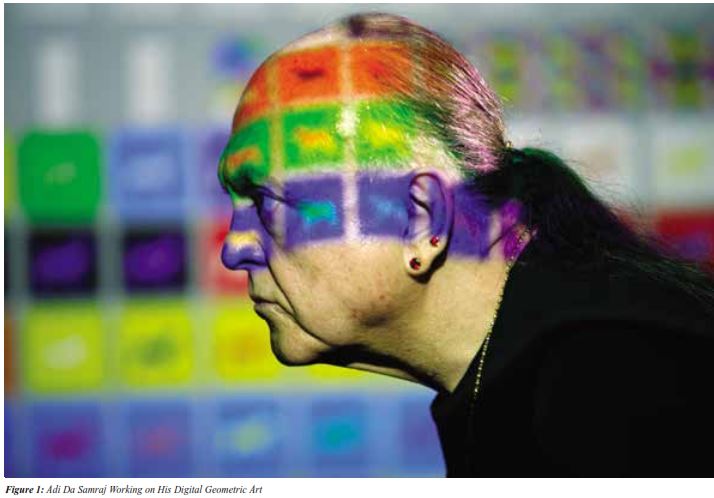

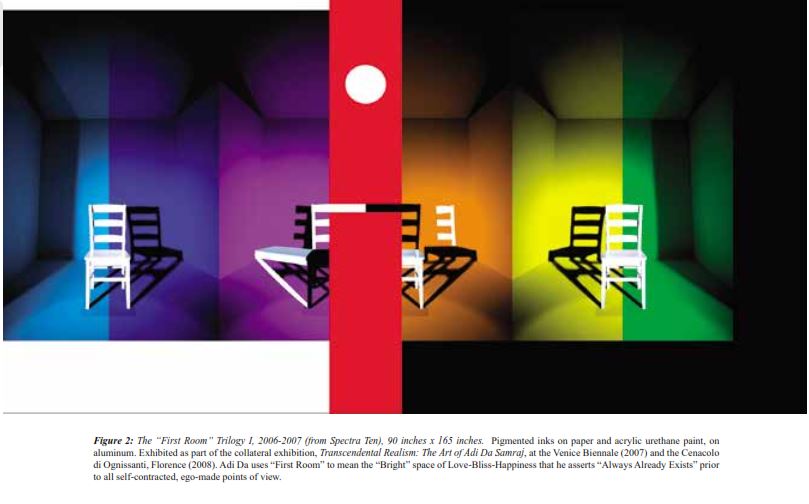

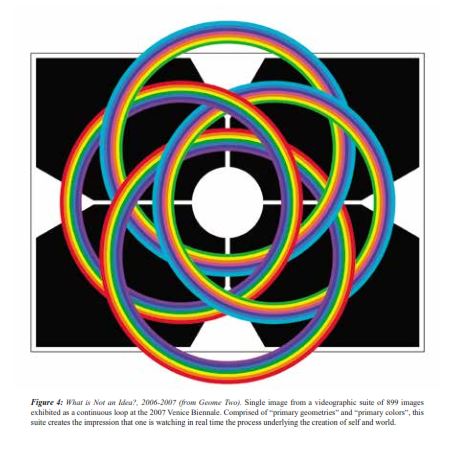

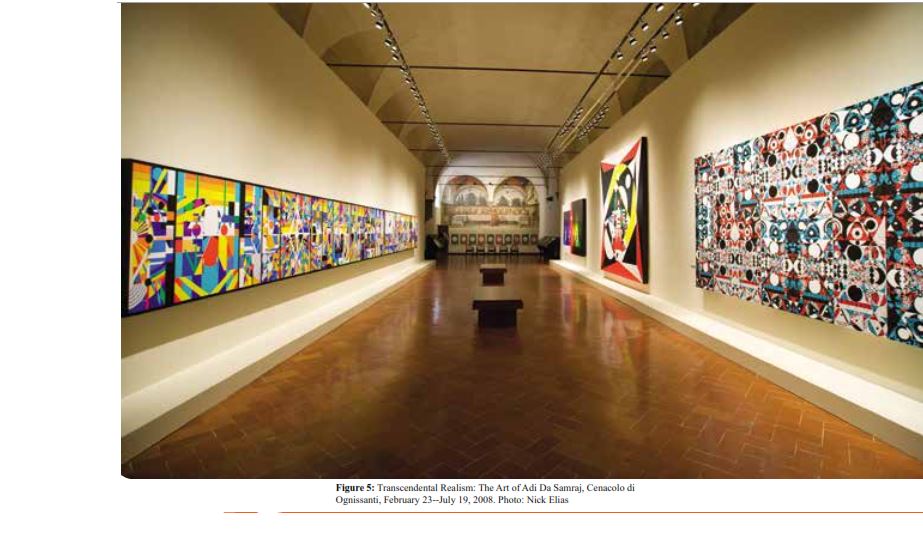

The spring 2008 exhibition in Florence, Transcendental Realism: The Art of Adi Da Samraj, offered visitors an opportunity to experience four selections of Adi Da’s aperspectival art that were originally shown at the 2007 Venice Biennale. (See Figures 2,3, and 4) They were displayed in the Cenacolo di Ognissanti, a beautiful space which contains one of the finest examples of the perspectival art of the Renaissance, The Last Supper (1480), a fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio. (See Figure 5) Thus, at this exhibition it was possible, within the confines of a single room, to experience two radically different visions of art, consciousness, and reality which have arisen out of two very different historical epochs.

The Last Supper

Ghirlandaio’s beautiful fresco of The Last Supper fills the short end of the long narrow refectory at the Ognissanti church. (See Figure 6) While its content is still religious in nature, it is a paradigmatic example of what Adi Da calls perspectival “ego-art.” Painted as an illusionistic extension of the actual space of the room, this image presents the traditional scene of Jesus and the apostles gathered around a

table partaking of Christianity’s first sacramental meal. It is rendered in the same style and in the same colors as the room itself. The human figures and material objects are realistically represented as three-dimensional physical bodies, receiving light from their painted windows and casting the appropriate shadows. Beyond the arches of this painted room one can see realistically rendered but highly symbolic trees, birds and a calm, cloud-filled sky. One has the sense of looking beyond the real room and through the virtual space of the fresco intoa “real” outside world.

The effect of Ghirlandaio’s perspectival illusion is to create the impression that the figures in the Gospel story are actually present in the same space in which the viewer is located. By means of perspective and realistic forms of material representation, the barriers between real space and virtual space, sacred space and profane space, times past and times present are magically dissolved to create a new unified spatio-temporal reality.

Looking at Ghirlandaio’s fresco, one can readily see that the surface of perspectival art such as this is, just as Alberti says, a kind of window which looks out onto a purportedly “objective” outside world. The space beyond this window, however, does not include the viewer, who always remains detached, floating somewhere outside the picture. If one is attentive to the actual experience of The Last Supper, it is also possible to feel how one’s ordinary, taken for granted sense of being a separate skin-bound self existing within an objective, all-surrounding outside world (not-self) is magnified by means of perspective.

As Adi Da observes, this reinforcement through art of “point of view” consciousness comes with a hidden cost. “When one looks at perspectivally-based image-art, one is constantly being reminded of oneself, constantly being relocated in one’s own presumed separateness. One is, in effect, constantly walking into one’s own face. Thus, perspectivally-based image-art is inherently Narcissistic art, regardless of its apparent ‘subject’ matter.”

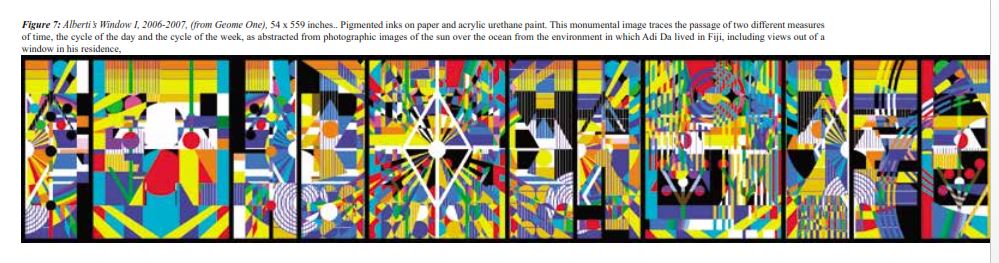

He explains: “I have given the title ‘Alberti’s Window’ to the suite Geome One as a means of pointing out that the image-art I make and do is, in fact, not Alberti’s kind of space, not the traditional space of Western art—which (first) ‘objectifies’ the surface of the artwork, and (then) uses various devices to draw the ‘viewer’ into the ‘objectified’ surface.”

Adi Da began the piece called Alberti’s Window I by making photographs of the environment in which he lives, including views looking out of a window in his residence in Fiji. Using these images “as a visual starting point—like a sketchbook, and a key to unlock feeling memory”, he proceeded to make computer-generated images in response to the image-content of his photographic “sketches”.

The final image developed by means of a spontaneous response to each iteration of the developing image itself.

While meaning is maintained, in part, by Adi Da’s constant reference to the original photographs taken at the beginning of the process, the forms and colors of Alberti’s Window I also embody the fundamental principles of what Adi Da calls “Reality Itself”, which, according to him, is what the world is before it is perceived by any “point of view” of any self-contracting ego-“I”. While it is clear why and how linear perspective makes use of geometry to create its spatiotemporal illusions, it is not so readily apparent why or how Adi Da Samraj used geometry to create order and meaning in his art. Based on his own experiences in deep meditation, Adi Da observes that the structure of human perception and the structure of the manifest world itself are both rooted in the underlying presence and ceaseless play of primary forces and geometries.

He used geometry as his primary means of artistic expression in Alberti’s Window I, and his other aperspectival geometric art, because he believed that this abstract formal language speaks wordlessly and universally to the underlying order of both self and world.6

Thus, it is possible to tacitly feel, when standing in the presence of this monumental work, that one is perceiving a meaningful field of generative forces rather than a meaningless display of geometric forms.

One experiences in this work the essence, rather than merely the outcome, of nature’s processes of being and becoming.

But what of Adi Da’s use of strong, radiant, and light-filled color in Alberti’s Window I? Starting with his Spectra Suites in 2006, Adi Da exclusively used a palette of “pure” colors in order to orchestrate very specific effects: “A pure color is a vibration…a piece of the spectrum of visible light…Color is not arbitrary. It must be exactly right for each image in particular. Color has emotional force. Colors in relation to one another generate, by that relatedness, different modes, or tones, of emotional force.” He further explains that, like primary geometry, color also “has meaning in the nervous system, in the folds of the brain. That meaning is not something that can altogether be stated verbally, but meaning is inherent in color.”

Such a bold intention would suppose, at the very least, that the perceptible visual patterns, colors and subtle qualities of images such as Alberti’s Window I would be homologous to what he claims is the very nature and structure of “Reality Itself”.

cannot be said, Adi Da does indicate that “Reality Itself”, or “That Which Is Always Already the Case” has, “no ‘thing’ in it, no ‘other’ in it, no separate ‘self’ in it, no ideas, no constructs in mind or perception, and, altogether, no ‘point of view’.”

Does Adi Da’s art measure up to this standard? When first gazing upon Alberti’s Window I, the mind and the mind’s eye race to discover the hidden order that structures and, therefore, explains the power and beauty of the work.

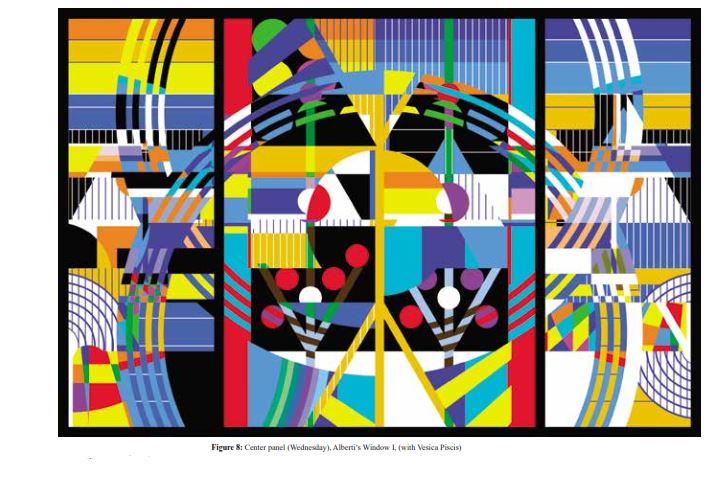

One wants to get a handle on it, figure it out, domesticate its strangeness, reduce its complexity to something simpler, something that can be named and known. And at first, it seems that it might be possible to do so. Yes, there are indeed organizing structures to be observed. First of all, one notices that the great length of the piece is divided into seven identically sized panels, each of which has a larger central panel and two smaller side bays. The central panel, which has two large multi-colored circles intersecting to create a large eye-like vesica piscis, appears at first glance to give the work a kind of overall symmetry. (See Figure 8) Yet, a closer look reveals that there is, in fact, no overall symmetry: the images to the left of the central panel are more complex and less clearly ordered than the panels on the right of it, which are calmer, less brightly colored, more highly ordered and more figural. Thus, while each individual panel might remind one of the daily movement of the sun from morning to night, the temporal rhythm of the overall piece is directional as one moves from left to right, rising to a peak of balanced harmony in the center and falling back to a state of subdued calm and greater formal simplicity at the end. One senses in this pattern the presence of both circular time and linear time. With this insight, the thinking, grasping mind has something else to say about this enormous image, something else tohold on to.

The longer one spends with Alberti’s Window I, however, the more it becomes evident that every apparent ordering system is always also inevitably undermined. Exceptions to the rule are the rule. Every instance of local order arises only to dissolve again into a playfully creative chaos, which is a paradoxical kind of order that can be felt but never fully described. Eventually, one comes to the conclusion that in Alberti’s Window I there is order without system, in a work of art that is a living field of dynamically balanced polarities.

Symmetry and asymmetry, cool colors and warm colors, horizontal lines and vertical lines, rising forces and falling forces, circular forms and angular forms, advancing colors and retreating colors, pure geometries and indefinable shapes are woven together to create an image that is never at rest, yet,

always seems to be calm and centered. One slowly comes to the understanding that in Alberti’s Window I there are, indeed, no separate forms, and that a mysterious sense of creative order and a prior, underlying unity are all-pervading. Finally, when the compulsive search for order, purpose and meaning falls completely away, and one simply becomes mindless in the face of the overwhelming size, seductive beauty and incomprehensible complexity of this monumental work of art, one discovers that Alberti’s Window I cannot be defined or grasped by the mind’s eye or the ego’s “I”. The only possible response that is left is to surrender, simply and spontaneously to the allure of the piece and to wander happily without any “point of view” in the dimensionless spaces of this primal landscape, which is a reality that is both familiar and strange. Forms are then felt with the whole body, colors are sensed as temperatures and qualities of being, and order is experienced as what Adi Da describes as a “nonnecessary” and “non-binding” appearance arising out of an unseen reality both infinite and filled with light. In this realm and state, there is no time and there is no space. This experience brings a sense of freedom that is unthreatened and unthreatening. There is only pleasure and delight that spontaneously and naturally arises as soon as the frenzy of seeking and the need to name and control is forgotten. This is

the experience that Adi Da describes as “aesthetic ecstasy”, which is his true purpose in creating his art:

The living body inherently wants to Realize (or Be One With) the Matrix of life. The living body always wants (with wanting need) to allow the Light of Perfect Reality into the “room”. Assisting human beings to fulfill that impulse is what I would do by every act of image-art. My images are created to be a means for any and every perceiving, feeling, and fully participating viewer to “Locate” Fundamental and Really Perfect Light—the world As Light, conditional (or naturally perceived) light As Absolute Light. Ultimately, when “point of view” is transcended, there is no longer any “room” or (any separate “location” and separate “self”) at all—but only Love-Bliss- “Brightness”, limitlessly felt, in vast unpatterned Joy.