Paul Jackson Pollock /ˈpɒlək/ (January 28, 1912 – August 11, 1956) was an American painter

Jackson Pollock was a titan of Abstract Expressionism and one of the most famous American artists of the 20th century. He pioneered an acrobatic process which produced large-scale, gestural, all-over drip paintings, or “action paintings.” Before developing his iconic style, Pollock worked for the WPA Federal Art Project and studied under artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, who influenced Pollock’s signature experiments with paint and material. During his lifetime, Pollock exhibited widely in New York and beyond. Since his untimely death in 1956, his work has been shown at institutions including the Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, Guggenheim Museum, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Kunstmuseum Basel, and his paintings have sold for tens of millions of dollars on the secondary market. His work belongs in esteemed collections worldwide.

Reference:

Artsy.net

www.jackson-pollock.org

Wikipedia

Jackson Pollock’s first fully mature works – dating between 1942 and 1947 – use an idiosyncratic iconography he developed in part as a response to Surrealism. Arising from this confluence of abstraction and figuration are Pollock’s breakthrough works, commonly perceived as pure abstraction and made over the course of an explosive period between late 1947 and 1950, as in Number 18 (1950).

Pollock had created his first “drip” painting in 1947, the product of a radical new approach to paint handling. With Autumn Rhythm, made in October of 1950, the artist is at the height of his powers. In this nonrepresentational picture, thinned paint was applied to unprimed, unstretched canvas that lay flat on the floor rather than propped on an easel. Poured, dripped, dribbled, scumbled, flicked, and splattered, the pigment was applied in the most unorthodox means. The artist also used sticks, trowels, knives, in short, anything but the traditional painter’s implement to build up dense, lyrical compositions comprised of intricate skeins of line. There’s no central point of focus, no hierarchy of elements in this allover composition in which every bit of the surface is equally significant. The artist worked with the canvas flat on the floor, constantly moving all around it while applying the paint and working from all four sides.

Blue Poles, originally titled Number 11, 1952, is an abstract expressionist painting and one of the most famous works by Jackson Pollock. It was purchased amid controversy by the National Gallery of Australia in 1973 and today remains one of the gallery’s major holdings.

At the time of the painting’s creation, Pollock preferred not to assign names to his works, but rather numbers; as such, the original title of Blue Poles was simply “Number 11″‘ or “No. 11” for the year 1952. In 1954, the new title Blue Poles was first seen at an exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery and reportedly originated from Pollock himself.

In the early 1940s Pollock, like many of his peers, explored primeval or mythological themes in his work. The wolf in this painting may allude to the animal that suckled the twin founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, in the myth of the city’s birth. But “She-Wolf came into existence because I had to paint it”, Pollock said in 1944. In an attitude typical of his generation, he added, “Any attempt on my part to say something about it, to attempt an explanation of the inexplicable, could only destroy it” The She-Wolf was featured in Pollock’s first solo exhibition, at Art of This Century gallery in New York in 1943. MoMA acquired the painting the following year, making it the first work by Pollock to enter a museum collection.

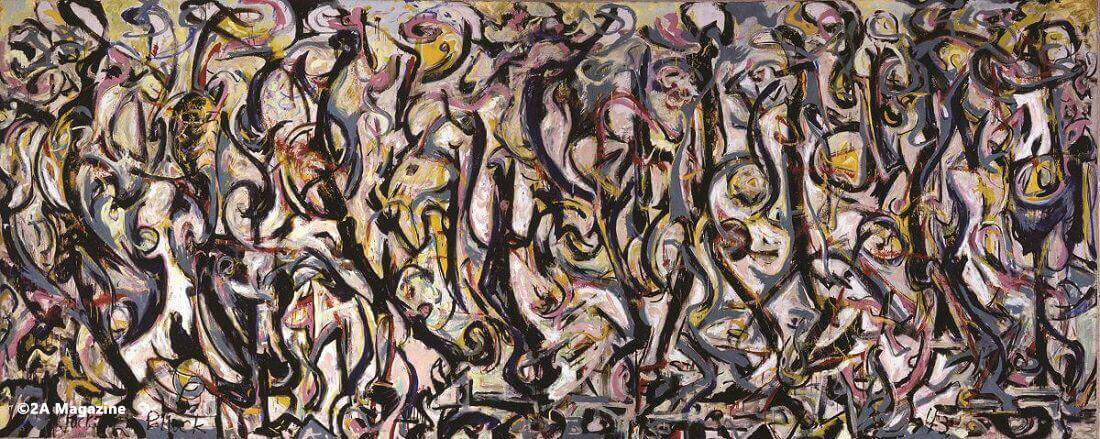

When Pollock received the commission to create a mural for the entry to Peggy Guggenheim’s new townhouse, he had Howard Putzel, Guggenheim’s secretary-assistant, to thank. Putzel had urged Guggenheim to give Pollock a project that would unleash the force he perceived in Pollock’s smaller-scaled easel paintings. For her part, Guggenheim was eager to present in her home a symbol of support for the new American brand of art she was beginning to champion in her gallery. The choice of subject was to be his, and the size, immense 81 1/4″ x 19′ 10″, meant to cover an entire wall. At the suggestion of Guggenheim’s friend and advisor Marcel Duchamp, it was painted on canvas, not the wall itself, so it would be portable. Pollock wrote of his commission that it was: “…with no strings as to what or how I paint it. I am going to paint it in oil on canvas. They are giving me a show on November 16 and I want to have the painting finished for the show. I’ve had to tear out the partition between the front and middle room to get the damned thing up. I have it stretched now. It looks pretty big, but exciting as all hell.”

It was not for nothing that white was chosen as the vestment of pure joy and immaculate purity. And black as the vestment of the greatest, most profound mourning and as the symbol of death. The balance between these two colors that is achieved by mechanically mixing them together forms gray. Naturally enough, a color that has come into being in this way can have no external sound, nor display any movement. Gray is toneless and immobile. This immobility, however, is of a different character from the tranquility of green, which is the product of two active colors and lies midway between them. Gray is therefore the disconsolate lack of motion. The deeper this gray becomes, the more the disconsolate element is emphasized, until it becomes suffocating. ”

– Wassily Kandinsky, On the Spiritual in Art