Chris Ofili

British, b. 1968

Chris Ofili’s playful, kaleidoscopic canvases

consider desire and identity, especially as related to African diasporic traditions. The artist’s aesthetic and conceptual influences are legion: A member of the Young British Artists, Ofili has referenced Zimbabwean cave paintings, blaxploitation films, and Catholic iconography. He composes his lush, dense canvases from collage, glitter, and—perhaps most famously—elephant dung. Ofili studied at the Chelsea School of Art before receiving his MFA from the Royal College of Art. He has exhibited extensively in New York, London, Paris, Miami, Berlin, Tokyo, and Los Angeles. Ofili has presented at the Venice Biennale twice, in 2003 and 2015, and in 1998, he won the Turner Prize. His work has sold for seven figures at auction and belongs in the collections of the British Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Tate, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Walker Art Center, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

This life-size painting shows an abstracted black Virgin Mary with a vibrant yellow background. One breast is exposed, as is traditional in classical depictions of the Virgin Mary and, less traditionally, is embellished with elephant dung. All around her flutter butterflies made from buttocks and vaginas cut from pornographic magazines.

The painting is Ofili’s attempt to deal with his childhood questions about race and virgin mothers, in particular which women are permitted to be holy, to be pure, and to be considered ‘good mothers’. The black Madonna is often seen in Catholic iconography in Africa and the Caribbean, although Ofili’s depiction is an intentionally provocative rendering of the subject. He said: “When I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are. Mine is simply a hip-hop version.”

Afrodizzia is a colorful abstract composition embellished and propped up with elephant dung reinforced with polyester resin. Multiple heads from Blaxploitation movies are collaged into the vivid colors, glitter, and multi-layered paint effects alongside well-known black figures, which then have Afros comically pasted around their faces. The title is a play on the word ‘aphrodisiac’, which references a substance ingested to increase the libido, and again complicates relationships between blackness and sexual desire.

Blaxploitation cinema emerged out of Black Power and civil rights movements in the 70s and it remains a controversial genre, which both challenges and reinforces racial stereotypes. Despite its difficulties – in particular treatment of black women, and reinforcing ‘gangster’ stereotypes – Blaxploitation was an angry celebration of Black America and this complexity is reborn as a contemporary festival of Black cultures in Afrodizzia.

In this moving painting, Ofili depicts the weeping profile of Doreen Lawrence, whose son Stephen Lawrence was murdered by a racist gang in London in 1993. There was a massive outcry about the police’s failings to properly investigate the case, particularly in black communities in London and the public inquiry that followed found the Metropolitan police force to be institutionally racist. In each of the tears shed by the grieving mother is a collaged image of her son’s face, while the words ‘R.I.P. Stephen Lawrence’ are just discernible beneath the layers of paint.

This narrative work uncompromisingly depicts grief and pain, not only of Doreen and Stephen Lawrence, but all victims of racist violence. Ofili said: “This kid had been killed by white racists. The police had fucked up the investigation, and the image that stuck in my mind was not just his mother but sorrow – deep sorrow for someone who will never come back. I remember finishing the painting and covering it up, because it was just too strong.”

This work is unlike anything you might expect to see in a gallery! The vast canvas is filed with an enormous black penis, with grinning cartoon minstrel face and an Afro. Bizarre crab-like creatures made of collaged and mismatching heads and legs surround it. Three balls of elephant dung sit at the bottom of the work.

In the early 1900s, minstrel shows were extremely popular in America, in which white performers would wear blackface including exaggerated huge lips and pitch-black skin to caricature black people. Elements of this practice still exist in more contemporary society, as in gollywogs and ‘coon’ cartoons. One of the most pervasive racist stereotypes is that of the sexually virile, well-endowed black man. This stereotype contributed to false rape accusations and lynching historically and is still perpetuated today as a reason to fear young black men.

The Upper Room installation of 13 paintings is an explosive rendering of the sacred and secular in the context of human and non-human worlds. Each painting features a rhesus monkey, the primate that most closely resembles humans. 12 canvases are arranged equally on either side of a larger one, suggesting Christ and his apostles, as they are historically depicted in paintings of the Last Supper. The title also references this Bible story; the Upper Room is where Jesus’ last supper before crucifixion was held, alongside 12 apostles.

The paintings were exhibited at the Tate in a quiet, dark, chapel-like room designed by friend and architect David Adjaye. Ofili wanted the venue to feel like a space of worship and the paintings were illuminated so they would refract colored light, as if stained-glass windows.

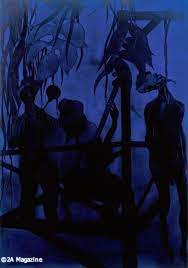

Compared to the brightness, optimism and vivid color of Ofili’s earlier works, the Blue Rider series provides a marked departure. In tribute to Wassily Kandinsky’s and Franz Marc’s Der Blaue Reiter movement, this series of dark canvases abandon the cheerful style of Ofili’s 1990s works. Iscariot Blues shows two figures playing musical instruments while a third hangs from a gibbet under the cover of darkness. It is uncomfortable to look at, as the hanged figure’s head snaps back from the pressure of the rope. It is also difficult to decipher; the tones and colors so dark it is hard to discern the figures.

The work is drawn from the Trinidadian folklore of the island he has made his home where, at carnival time, people dress up as blue devils and terrorize onlookers with blood, snakes and frogs. Tradition dictates that these blue ‘devils’ have permission to behave in a menacing and intrusive manner that would normally be prohibited by society. In this series, Ofili associates these ‘blue devils’ with the ‘boys in blue’, the British police, explicitly challenging police violence in the UK. The images in the painting are rendered in such darkness they are barely visible, suggesting conduct that occurs in a state of near invisibility.